I have been following the work of Megan Evans (who is PhDing at at the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia) for quite a while, now. Not only in personal communication or via her publications (by the way, Megan, I should tell you, I admire you for your diligence — you’ve been very busy publishing those last months) — but also via her blog, entitled “Ravings and research on environmental policy”. This has given me some interesting views on offsets the “Aussie” way (sorry, if that sounds weird from a non-Australian).

I have been following the work of Megan Evans (who is PhDing at at the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia) for quite a while, now. Not only in personal communication or via her publications (by the way, Megan, I should tell you, I admire you for your diligence — you’ve been very busy publishing those last months) — but also via her blog, entitled “Ravings and research on environmental policy”. This has given me some interesting views on offsets the “Aussie” way (sorry, if that sounds weird from a non-Australian).

Now, some days ago Megan has launched a four part series of posts outlining the research journey of her PhD so far. Because that is particularly dense information and an interesting read, I’ll share some of that here. She describes the line of her reasoning from the initial interest in the outcomes of biodiversity offset policy over the tricky path of how to do policy analysis and evaluation back to the question why biodiversity offset policies are hardly ever evaluated despite their expansion.

Post 1: Seeking evidence to inform the biodiversity offsets policy debate

When I first embarked on my PhD research, my main interest was in trying to learn about what outcomes had been delivered by biodiversity offsetting policies. There were a few reasons for this. First, I knew that biodiversity offsetting was becoming increasingly popular. At last estimate, 45 countries have some form of offsetting or ‘no net loss’ policy, and another 27 countries have policies in development (Madsen et al. 2011). I’d also noticed that offsetting was being proposed as a mechanism for expanding the network of protected areas in my home state of Queensland – a policy which I’d expressed some concerns about at the time. But probably the main motivation for my research question came from the often polarized discourse that surrounds the use of biodiversity offsetting. […]

I think that much of the discussion around biodiversity offsetting, and indeed the use of economic or market based instruments in biodiversity conservation more generally, falls into two fairly divergent narratives. One is primarily concerned by opportunities; whereby offsets could provide more efficient and effective policy outcomes than traditional regulation, deliver “win-win” outcomes for conservation and the economy, and may deliver social and cultural co-benefits. The other is chiefly concerned with risks; that offset calculations will fail to capture all the values we care about, that offsets are merely “symbolic policies”, and more general ethical concerns over the commodification of nature.

The problem with having a policy debate which focuses on such divergent and often irreconcilable views, is that it provides no clear path forward in a political environment where offset policy is, and has been for some time, the policy of choice for democratically elected governments. Given this reality, how does one pragmatically move forward?

This is why I was interested in examining the evidence. […] As I looked further into the issues, however, I learned that answering my research question might not be so feasible after all (or, indeed, the most interesting question to ask).

Read more here.

Post 2: Evaluating environmental policies: what, how and why

A key criticism of biodiversity offsetting is that the measures implemented on-ground to compensate for impacts elsewhere often fail to deliver their intended environmental outcomes – or in fact, are never actually implemented as promised. Clearly, there’s a need to know what, if any, outcomes have been delivered by biodiversity offset policies, and ideally to understand some of the reasons as to why a particular result is being delivered. This is where policy evaluation comes in.

Now, I want to point out right now that there is a positively e n o r m o u s literature on policy evaluation, spanning many disciplines and schools of thought.[…]

First, I’ll clarify that in my research I’m interested in on ex post or retrospective evaluation, where the focus is on determining the merits of a policy that has already been implemented, whereas ex ante or prospective evaluation is an analysis of the merit a policy prior to implementation.[…]

The purpose of an evaluation may not simply be to determine what outcomes (intended and unintended) have been delivered by a policy, but could also want to examine the policy design, the process of implementation, or to attempt to establish the impact of the policy relative to what would have happened in its absence. […]

A key concern is establishing the counterfactual – that is, what would have happened in absence of the policy intervention? This means trying to eliminate all possible confounding variables. Nice examples are this paper by Greenstone (2004) which asked whether the US Clean Air Act actually did lead to the massive observed reduction in sulphur dioxide emissions (spoiler alert: probably not), and Bottrill et al (2011) which found that recovery plans didn’t actually lead to threatened species recovery in Australia.

Read more here.

Post 3: Evaluation is important, so why don’t we do it more often?

I think it’s pretty well established that evaluation is an incredibly important activity, as it’s really the only way to find out whether or not a policy is meeting it’s intended goals. Not only whether the these goals are being met (effectiveness), but whether or not the policy is efficient, if any unintended outcomes have occurred, and whether there are any opportunities for policy improvement.

A number of keys papers have examined the use of evaluation in the environmental and conservation policy spaces in the last 10 years, and many have provided guidance on how to conduct evaluations in different circumstances. Possibly the most prominent example is Ferraro and Pattanayak’s 2006 “Money for Nothing” paper, which introduced key concepts and terms from the evaluation literature to a broader audience, and called for a greater focus on evaluating the impact of conservation policies. More recently, Keene and Pullin (2011) argued for an “effectiveness revolution” in environmental management, and Miteva and others (2012) called for what they termed “Conservation Evaluation 2.0″ – more urgent efforts to evaluate conservation policies in more locations. […]

So, we have the know-how, and the need to know whether the huge investment into conservation globally is achieving results – surely we should be doing evaluation all the time, right?

Unfortunately, this is not really the case. In their review of studies which have evaluated the performance of conservation policies, Miteva and others (2012) found that “…credible evaluations of common conservation instruments continue to be rare”. […]

So, given all that, why on earth are we not evaluating more often?

1) It’s (methodologically) hard

Let’s face it, it’s pretty hard to do an evaluation if you don’t have any data available to do such analysis. And when we’re working in the environmental space, collecting suitable data and doing an evaluation just becomes even harder. Ecological systems are incredibly complex and difficult to measure – there are long time-lags, non-linear responses, and very large spatial scales to consider – to name just a few issues.[…]

2) Shouldn’t we be spending money on management, rather than monitoring (or evaluating)?

In the face of scarce data, it’s often easy to recommend that we just need to make a greater effort to collect it. In some cases this may be true, but I think it’s often more complex than this, and we need to think carefully about the time and resources required to collect data and whether those resources could be better used for other activities (see our recent paper in Conservation Biology for a discussion of this).[…]

3) Many actors, and many different objectives

Environmental policy doesn’t exist in a rational, value-free vacuum where the only considerations are the environmental assets we’re trying to protect or manage. It operates within a complex socio-political system, containing a range of individuals and organisations with varying motivations and objectives.

Organisations who are responsible for designing and implementing policies, whether they be government or non-government, can be reluctant to evaluate how successful those policies were, as it opens them up to criticism if the policy was not successful. There often needs to be a lot of political will and a strong commitment to accountability for evaluation to occur.[…]

So, these are some issues which are considered as possible barriers to evaluation of environmental policy in general. What about biodiversity offsetting specifically? Are there any unique challenges to consider?

Read more here.

Post 4: A framework to analyse the effectiveness of biodiversity offset policy

I began my PhD by asking the question, “What environmental outcomes are being delivered by biodiversity offset policies?”.[…]

In finding that answering the “What…?” this question was actually going to be extremely difficult, I asked “Why is there a lack of information on what outcomes are being delivered by biodiversity offset policies?”. Perhaps there are particular issues acting as barriers to evaluation. If so, what could these be?

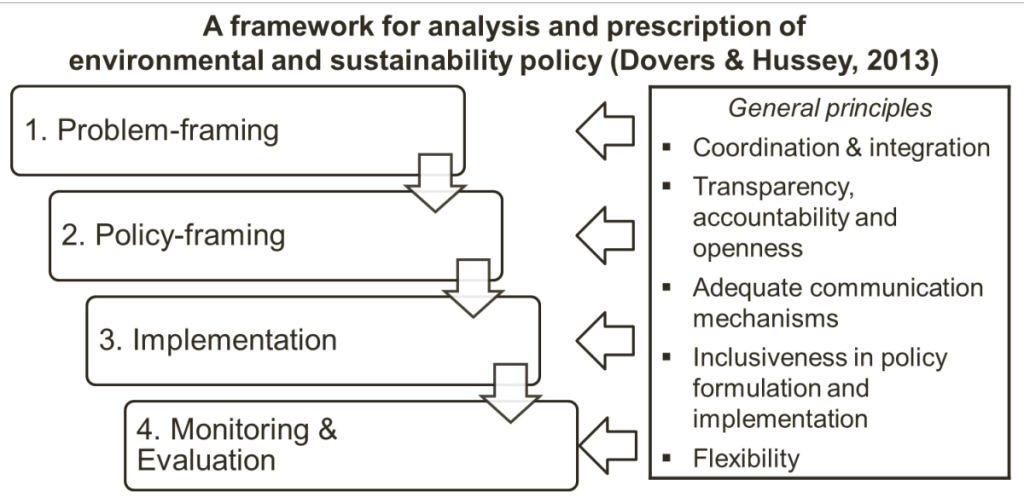

Indeed, if we step back a bit, and consider that monitoring and evaluation is a key component of good public policy (Dovers and Hussey, 2013), then this could provide a useful framework to identify a range of issues which ultimately influence what environmental outcomes are delivered by biodiversity offsetting policy.

If we think about what makes a “good” biodiversity offset policy, there has been a lot of discussion in the literature about what should be the some of the key policy principles (e.g, no-net-loss, like-for-like). This research speaks to how the policy is framed and what the goals could be (item 2 in the figure), but not necessarily how it should be implemented, monitored or evaluated.

There’s also been a lot of research which has been focused on developing and refining offset metrics, which can most accurately measure how much and what kind of biodiversity values are to be lost from an impact site, and what would be an adequate compensation at the offset site. Considering things like time lags, uncertainty and the specific biodiversity features being impacted is really important (see our recent paper on the EPBC Act offset metric, and a related blog post).

Although the availability of credible and scientifically robust offset metrics is obviously an essential component of formulating biodiversity offset policy, there are a range of issues (which are often non-ecological) which influence the environmental outcomes likely to arise from offset policy. We can conceptualise these issues as falling into one of three domains – measurement, institutional and organizational. […]

Read more here.