This is a guest post by Carlos Ferreira, Research Assistant in the Center for Business in Society at Coventry University. He can be reached at carlos.ferreira@coventry.ac.uk.

It is the expression of the author’s thoughts and experiences and as such is acknowledged as a fruitful contribution to the discussion on biodiversity offsets. If you want to react or clarify your own position (underpin or disprove Carlos’ reasoning), please leave a reply below!

Offsetting biodiversity: widespread and varied

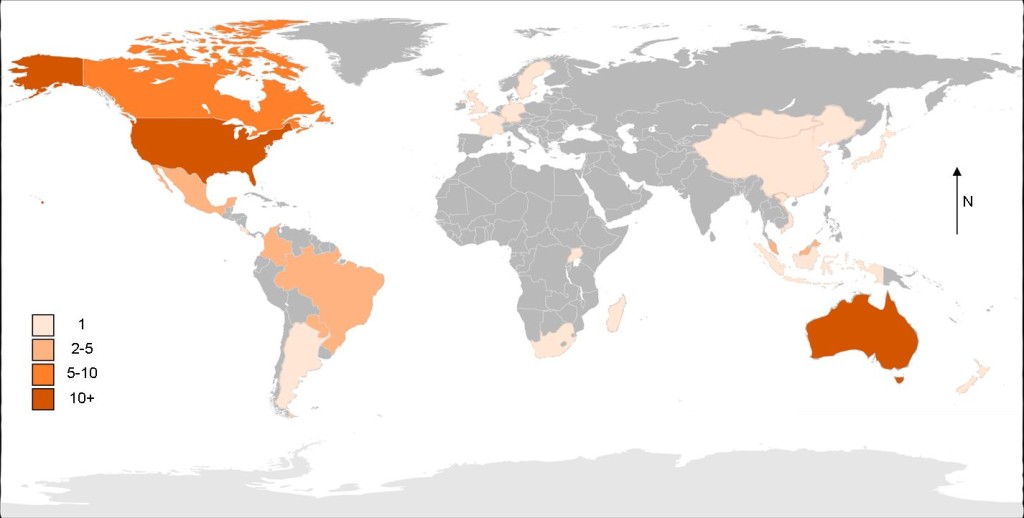

A visit to the SpeciesBanking website shows that the practice of compensating for biodiversity losses is widespread. Offsetting biodiversity losses is an increasingly important mechanism for balancing out development and conservation, with more and more governments creating regulation or issuing guidance for its usage, often in the context of planning regulations. In fact, in several countries it is possible to observe that various offsetting programmes are currently in operation. The figure illustrates this, highlighting the number of official biodiversity offsets programmes per country.

Each of these individual examples of biodiversity offsets is predicated on specific objectives, specific regulation and a specific set way of doing things; no two programmes are the same. In common, the various individual programmes share the existence of regulator guidance specifying that biodiversity damage must be compensated, and the idea of no net loss of biodiversity. However, there is currently no standard form of calculating biodiversity losses and gains; even the Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme’s 2012 Standard on Biodiversity Offsetting recognised this, advocating that measurements should adaptable, with individual mechanisms for demonstrating equivalence between biodiversity lost and gain. As a result, the various biodiversity offsetting programmes remain experimental.

Dipping a toe: the diverse tools of biodiversity offsetting

Part of the reason for the difficulty in creating standard biodiversity measurement tools lies with what is being measured: biodiversity is complex, and can refer to aspects of nature which go from the genetic level to the number of individuals in a species, or the relationship between species in an ecosystem. From the point of view of ecological sciences, this creates the problem of defining what is meant by “biodiversity” in each specific programme, in order to produce an appropriate tool for each case.

The second problem lies with what aspects of biodiversity is under analysis in each case. For example, in the US Mitigation Banking programme, compensation is generally sought when individuals of a listed species are lost; in Germany, the focus is on the improvement of biodiversity indicators in a given area; and in the UK, the focus is on compensating for losses of pre-defined ecosystem types. Obviously, most of the tools developed in one of these programmes are not usable in another.

The third and final problem is the existing trade-off between precision in measurement and usability of the tool. A more precise biodiversity measurement mechanism has a better potential when addressing the need to demonstrate no net loss of biodiversity, but it makes it more difficult to achieve that objective in practice. The resulting calculations can be so precise as to completely deny the possibility of compensating for biodiversity, by making biodiversity lost entirely unique and not liable to offsetting.

With all these issues associated in calculating no net loss of biodiversity, it would appear that biodiversity offsetting faces serious challenges. But are there new opportunities at the same time?

Current challenges, future opportunities?

For all the problems in developing calculation tools, the single greatest challenge for biodiversity off-setting comes from opposition at local level. Grassroots and NGO-led campaigns have successfully managed to communicate their negative opinions about biodiversity offsetting, through on-the-ground and online campaigns, and have in the process been noticed by the mainstream media. As a consequence, biodiversity offsetting promoters may be losing control of the message: while they have attempted to associate biodiversity offsetting as no net loss of biodiversity, opposition campaigners have framed it as a license to trash nature.

This doesn’t need to discourage promoters of biodiversity offsetting. Better quantification, with the explicit objective of demonstrating no net loss of biodiversity, is what distinguishes biodiversity offsets from other forms of compensating for negative nature impacts. The potential effects in simplifying the negotiations about appropriate compensation and achieving stakeholder buy-in are the ad-vantage of biodiversity offsetting over alternative mechanisms of obtaining compensation for biodiversity losses. And despite the ongoing problems with the tools to deliver this, biodiversity offsets still constitute one of the most thorough ways to balance out economic development and biodiversity conservation.